ABC News/Luke Bowden

ABC News/Luke BowdenFor months, an uncommon monument sat in an oak-lined sq. on the coronary heart of Tasmania’s capital: a pair of severed bronze toes.

A statue of famend surgeon-turned-premier William Crowther had loomed over the park in Hobart for greater than a century. However one night in Could, it was chopped down on the ankles and the phrases “what goes around” graffitied on its sandstone base.

It was a throwback to a different night time greater than 150 years in the past, when Crowther allegedly broke right into a morgue, sliced open an Aboriginal chief’s head and stole his cranium – triggering a grim tussle over the remaining physique components.

Tasmania had turn into the centre of coloniser efforts to eradicate Aboriginal individuals in Australia. And the sailor on the slab – William Lanne – was touted because the final man on the island, making his stays a twisted trophy for white physicians.

Some see Crowther as an unfairly maligned man of his time, and his effigy as an vital a part of the state’s historical past, warts and all.

However for Lanne’s descendants, it represents colonial brutality, the dehumanising fable that Tasmanian Aboriginal persons are extinct, and the whitewashing of the island’s previous.

“You walk around the city anywhere and you’d never know Aborigines were here,” Aboriginal activist Nala Mansell says.

Now the dismembered statue has turn into an emblem of a metropolis – and a nation – struggling to reckon with its darkest chapters.

The extinction lie

Few locations encapsulate the problem fairly like Risdon Cove – known as piyura kitina by the Palawa Aboriginal individuals.

Tucked beside a creek, a monument proudly marks it as the primary British settlement on what was then known as Van Diemen’s Land.

BBC/Andrew Wilson

BBC/Andrew WilsonFor Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals, although, this hillside on the outskirts of Hobart is “ground zero for invasion”.

“It’s the first landing and not coincidentally the first massacre [of our people],” Nunami Sculthorpe-Inexperienced tells the BBC one overcast afternoon.

Startled from their reverie, flurries of native hens – which piyura kitina is known as after – scatter over the mossy grass as we arrive.

A wallaby swiftly bounds in the direction of sparse gum timber. It’s from that path that Mumirimina males, girls and youngsters would have come down the slope on 3 Could 1804, singing as they hunted kangaroos.

They have been met with muskets and cannons.

The occasions of that day – and the dying toll – are disputed. What just isn’t contested is that this marked the beginning of a decided effort by British settlers to do away with the unique Tasmanians, 9 nations of as much as 15,000 individuals.

Warfare broke out and Aboriginal individuals have been hunted throughout the island, the survivors rounded up and despatched to what have been described as dying camps.

“If that happened anywhere in the world today, it would be referred to as ethnic cleansing,” says Greg Lehman, a Palawa professor of historical past.

Warning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers: this text accommodates pictures of somebody who has died.

Ripped from his homelands as a baby, Lanne survived two of these camps earlier than dwelling out his last years as a shipmate and beloved advocate for his individuals.

Even earlier than he died of illness in 1869, aged solely 34, letters present that highly effective males in Hobart had begun scheming.

“There’s no way that that young man was going to be allowed to lie in a grave. No way,” historian Cassandra Pybus tells the BBC.

The theft of Aboriginal stays had lengthy been normalised, she says, however reached a fever pitch in Tasmania because the variety of its authentic inhabitants dwindled.

Lanne’s cranium was sought to show since-discredited theories about Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals – that they have been the lacking hyperlink between people and Neanderthals, a definite race so primitive they didn’t even know the way to make hearth.

Earlier than he was buried, his fingers and toes would even be lower off and pocketed by physicians. Some historians say his grave was robbed as properly, and each bone in his physique taken.

Crowther at all times denied any involvement in stealing Lanne’s stays – his backers known as the allegations a witch hunt – however the city was horrified, and he was suspended from his honorary place on the hospital.

For First Nations individuals, who consider their spirits can solely relaxation as soon as returned to their land, what occurred was particularly distressing.

However inside two weeks, Crowther was elected to state parliament, and he’d quickly rise to be Tasmania’s premier for an unremarkable six months.

In contrast, Lanne’s cranium seems to have wound up on the opposite aspect of the globe at a UK college, and his individuals have been quickly declared extinct.

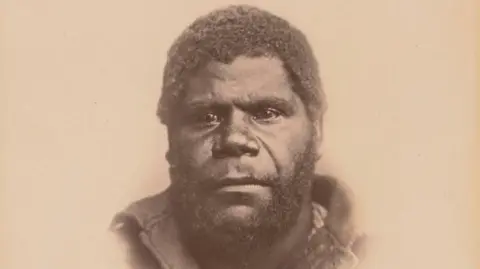

Nationwide Library of Australia/J. W. Beattie

Nationwide Library of Australia/J. W. BeattieBesides they weren’t.

As we speak’s Palawa individuals hint their ancestry to a dozen girls who survived, whereas different teams – which some don’t recognise as Aboriginal – additionally say they descend from a handful of people that managed to evade seize within the 1800s.

But, for the previous 150 years, Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals say they’ve been combating to be seen, within the historical past pages and in on a regular basis life.

The lie that they have been extinct is basically blamed on outdated views about ethnic id. However others say it was additionally a strategic determination – to disclaim Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals rights, and to snuff out their tradition.

The affect has been devastating. Many Palawa individuals converse of being persecuted for his or her Indigenous blood in a single breath and denied their id due to their white ancestry within the subsequent.

Even now, many really feel there are enormous swathes of their historical past lacking – or wilfully ignored.

Nala factors out all she was taught about Tasmanian Aboriginal tradition and historical past at her Hobart college was a short lesson on boomerangs and didgeridoos – though her individuals used neither.

And except for a strolling observe named after Truganini – Lanne’s spouse and a frontrunner in her personal proper – there are not any websites celebrating Aboriginal individuals across the metropolis.

“The way they tell stories about Aboriginal people… they want you to think that it’s somewhere really far away from where you are, and that it’s something that happened a really long time ago,” Nunami says.

Unimpressed, the 30-year-old historical past graduate began Black Led Excursions to fill the hole.

Black Led Excursions Tasmania/Jillian Mundy

Black Led Excursions Tasmania/Jillian Mundy“I realised that I was walking to work the exact same way Truganini used to walk her dogs. And I realised that my parents met at the pub where William Lanne died. I also realised that the Crowther statue was right next to my bus stop.

“And I believed: does everyone know that that is proper right here, the place we stay and the place we work?”

A disputed legacy

When unveiling the effigy in 1889, the then-premier said Crowther was not “an ideal man”, but one who spent his time doing good.

His scandal overlooked, until recently he was remembered for offering free health care to the poor.

That rankles Tasmanian Aboriginal people like Nala: “It is only a kick within the guts.”

As spokeswoman for the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, she led a renewed campaign to take down the memorial.

“To us, it might be no totally different to having a statue of Martin Bryant,” she says, referring to the gunman who massacred 35 people at nearby Port Arthur in 1996.

But some, like Jeff Briscoe – who lost the legal case to prevent the statue’s removal – believe the sculpture has priceless heritage value as the only memorial in the state “funded completely by the general public”.

“On the time, it was a big memorial and everybody was pleased with it. In 2024, ought to the perceptions of some individuals override all that?

“It’s not as if he was going around shooting people… he maybe had been involved in the mutilation of a body, but they all were.

“They’re bringing the bar down so low that no memorial from colonial occasions will probably be protected in Australia.”

BBC/Andrew Wilson

BBC/Andrew WilsonCassandra Pybus says there is no doubt that Crowther did mutilate Lanne, citing letters he wrote. However, she had argued, like Mr Briscoe, that taking down the statue would set a dangerous precedent, because “everyone was racist”.

She had wanted it to remain so the site could be used to educate people about how the first Tasmanians were treated.

The statue’s fate divided even Crowther’s living descendants, with some publicly supporting the calls for removal, and others distressed by them.

Hobart Lord Mayor Anna Reynolds says the council voted to remove the statue in 2022 “as a dedication to telling the reality of our metropolis’s historical past, and as an act of reconciliation with the Aboriginal group” – the first decision of its kind in Australia.

They did it after a rigorous consultation and with the support of the “silent majority”, she adds.

Ultimately, she says, the statue is a sign of how desperate Crowther was to repair his reputation, not his significance to the state: “[He’s] not that vital.”

But while the council worked through red tape, some grew impatient and took it down themselves.

ABC News/Luke Bowden

ABC News/Luke BowdenFor Lanne’s descendants, their relief at the long-awaited fall of the statue is tinged with pain. They feel Lanne has been reduced to his death.

“He had an entire life… and simply as he advocated for our individuals’s rights, we are going to advocate for his story to be remembered and him to be revered for who he was,” Nunami says.

Time for ‘truth-telling’?

The Crowther statue is not unique. Countless similar landmarks or monuments – which joke about massacres, include racial slurs or celebrate alleged killers – are still standing across Australia.

Many, like Greg, believe removing or renaming them could be a natural starting point for the “truth-telling” the country needs, to reconcile with its First Peoples, the oldest living culture on the planet.

“You’d assume that it was only a bunch of glad free settlers and not-so-happy convicts who jumped off the First Fleet… and bingo, there you’ve got obtained trendy Australia,” he says.

“For Australia to have an trustworthy and highly effective relationship with itself, it should have an trustworthy relationship with the previous.”

But after a proposal for an Indigenous political advisory body was defeated at a referendum last year, any movement towards a national truth-telling inquiry has stalled – though many states are setting up their own.

There are still many, like Jeff Briscoe, who believe a “truth-telling” process would be a divisive and unnecessary rehashing of the past – views echoed by a bloc of conservative politicians who also oppose a treaty.

“These days individuals need Aborigines to face in entrance of them and say welcome to our nation. They need us to bounce for them. They need us to show them our language. They do not thoughts if we put a few of our work within the mall,” Nala says.

“However if you happen to speak about… any sort of profit for the Aboriginal group, or taking again something that was stolen from us, it is a utterly totally different ballgame.”

However she is among those who feel like the tide is slowly turning.

“The Crowther statue… is the primary time I’ve ever thought, ‘Wow, white individuals – they’re beginning to get it’,” Nala says.

Blak Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian Mundy

Blak Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian MundyThe council was still deciding what should replace the sculpture when it met its unexpected end.

But many wanted the severed feet to remain in the square – as is – arguing they made a wryly “humorous” and “profound” statement.

However earlier this week, the council plucked the ankles from their perch, to reunite them with the rest of the effigy, citing heritage law requirements.

But Nunami says even the now empty plinth illustrates the story of Crowther and Lanne far better than the statue ever did.

“We get to say we, as the general public, learnt, we grew, and we modified the narrative of this place… Look right here, we lower that down.”