Nobody is definite why Stonehenge was constructed. This world-famous monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire is assumed to commemorate the lifeless, and is aligned with actions of the Solar and Moon.

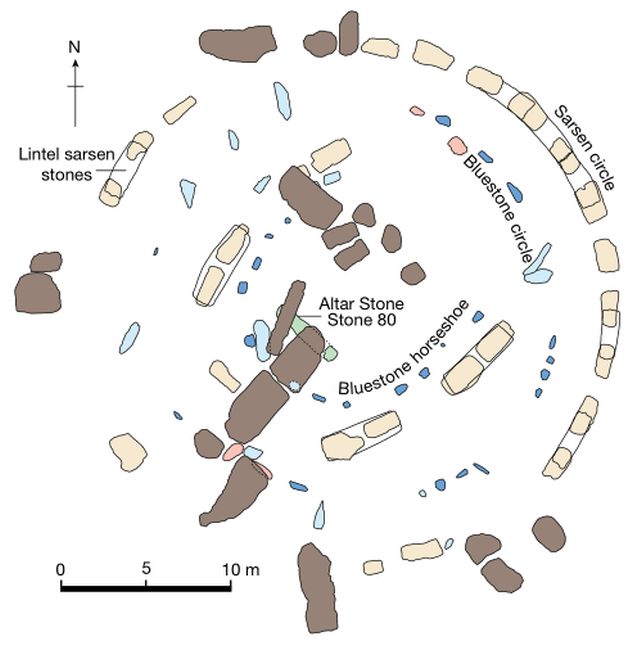

It consists of an outer ring and interior horseshoe of huge “sarsen” and “trilithon” stones, and an interior circle and horseshoe of smaller “bluestones”. It was inbuilt a number of phases between 5,000 and 4,200 years in the past.

The Altar Stone is likely one of the most enigmatic rocks at Stonehenge, and is usually grouped with the bluestones. Regardless of its identify (urged as its use by the architect Inigo Jones in 1620), its perform is unknown.

Mendacity flat on the coronary heart of Stonehenge, the six-tonne, five-metre-long rectangular Altar Stone is a grey-green sandstone, far greater and completely different in its composition from the opposite bluestones. So the place did it come from?

In our new paper printed in Nature, we’ve got traced the Altar Stone’s supply to north-east Scotland, that means it travelled at the least 430 miles (700km) to Salisbury Plain.

That is an unimaginable distance for Neolithic occasions, earlier than the wheel is assumed to have arrived in Britain. This beautiful discovery sheds new gentle on the capabilities and long-range connections of Britain’s Neolithic inhabitants.

Let’s overview what we all know, and the way we pinned down the area the place the Altar Stone originated. The massive stones at Stonehenge (sarsens) come from a couple of tens of miles away, however shifting these 30-tonne monsters was no imply feat in Neolithic occasions.

The smaller, unique bluestones are a unique story. Not native to Stonehenge, they weigh sometimes 1-3 tonnes and are as much as 2.5 metres tall. The Altar Stone, additionally not native, is twice the dimensions of the largest different bluestone. It’s not recognized when it arrived at Stonehenge, nor if it ever stood upright.

It was not till 1923 that geologist H.H. Thomas recognised that many of the igneous bluestones got here from the Mynydd Preseli in Pembrokeshire, south-west Wales. Our ongoing work has refined the sources of those igneous bluestones to particular person crags on the northern slopes of the Preseli hills.

Thomas additionally urged that the Altar Stone was in all probability taken from outdated crimson sandstone rocks discovered to the south and east of the Mynydd Preseli, on the presumed bluestone transport path to Stonehenge. The suggestion caught, and for 80 years went unchallenged.

Within the early 2000s, we began to look once more at supposed Altar Stone fragments in museum collections. Some fragments have been clearly wrongly recognized, so the time-consuming means of clarifying the scenario started.

Initially, the Altar Stone’s origin was now urged to be in western Wales, close to Milford Haven. However on the finish of the 2010s, we additional subjected its fragments to a wide range of geological analyses. These outcomes hinted at jap Wales or the Welsh borders as its supply, and discounted the west Wales origin.

However with out straight sampling the Altar Stone, how might we ensure that the museum fragments have been real? At present, we’re not allowed to knock lumps off Stonehenge, as occurred prior to now.

Novel approach

Within the early 2020s, we began utilizing handheld X-ray fluorescence evaluation, a non-destructive chemical analytical technique, on the Stonehenge bluestones – significantly on the numerous claimed Altar Stone fragments collected by older archaeological excavations. We then in contrast these with X-ray fluorescence analyses from the floor of the Altar Stone itself.

Sediment grains within the Altar Stone are cemented collectively by the mineral baryte, giving it an uncommon chemical composition that is excessive within the ingredient barium.

Just a few museum fragments have been similar to the Altar Stone – proving {that a} labelled fragment faraway from the Altar Stone in 1844 was real was essential. These few, treasured fragments could possibly be used for our research, so we did not want to gather new samples straight from the Altar Stone.

In the meantime, our scientific group now included geologists from England, Wales, Scotland, Canada and Italy. We had been analysing a spread of outdated crimson sandstone samples from throughout Wales and the Welsh borders, to attempt to discover a chemical and mineralogical match for the Altar Stone.

Nothing seemed related. By autumn 2022, we concluded that the Altar Stone couldn’t be from Wales, and that we would have liked to look additional afield for its supply.

On the identical time, an opportunity contact from Tony Clarke, a PhD scholar at Curtin College in Perth, Western Australia, provided a chance to go additional.

We invited the Curtin group to find out the ages of a sequence of minerals in two of the Altar Stone fragments, hoping this would supply info regarding its age and potential origin. This technique dates mineral grains within the rock and offers an age “fingerprint”, tying the grains to a selected area.

Our new research printed in Nature exhibits that the Altar Stone’s age fingerprint identifies it as coming from the Orcadian Basin in north-east Scotland. The findings of this age relationship are really astonishing, overturning what had been thought for a century.

It is thrilling to know that the end result of our work over virtually 20 years has unlocked this thriller. We will say with confidence that this iconic rock is Scottish and never Welsh, and extra particularly, that it got here from the outdated crimson sandstones of north-east Scotland.

With its origin within the Orcadian Basin, the Altar Stone has travelled a remarkably good distance – a straight-line distance of at the least 430 miles. That is the longest recognized journey for any stone utilized in a Neolithic monument.

Our analyses can’t reply how the Altar Stone received to Stonehenge. Forests posed one among a number of bodily obstacles to overland transport. A journey by sea would have been equally daunting. Equally, we can’t reply why it was transported there.

No matter archaeologists could uncover in future, our outcomes may have large ramifications in serving to understanding Neolithic communities, their connections with one another, and the way they transported issues over distance. In the meantime, our seek for an much more exact supply of the Altar Stone continues.![]()

Nicholas Pearce, Professor of Geochemistry, Aberystwyth College; Richard Bevins, Honorary Professor, Division of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth College, and Rob Ixer, Honorary Senior Analysis Fellow, Institute of Archaeology, UCL

This text is republished from The Dialog beneath a Inventive Commons license. Learn the unique article.