Imogen Foulkes

Imogen FoulkesThink about choosing up a pleasant juicy apple – however as a substitute of biting into it you retain the seeds and throw the remaining away.

That is what chocolate producers have historically carried out with the cocoa fruit – used the beans and disposed of the remaining.

However now meals scientists in Switzerland have provide you with a option to make chocolate utilizing all the cocoa fruit fairly than simply the beans – and with out utilizing sugar.

The chocolate, developed at Zurich’s prestigious Federal Institute of Know-how by scientist Kim Mishra and his crew contains the cocoa fruit pulp, the juice, and the husk, or endocarp.

The method has already attracted the eye of sustainable meals corporations.

They are saying conventional chocolate manufacturing, utilizing solely the beans, entails leaving the remainder of the cocoa fruit – the scale of a pumpkin and filled with nutritious worth – to rot within the fields.

The important thing to the brand new chocolate lies in its very candy juice, which tastes, Mr Mishra explains, “very fruity, a bit like pineapple”.

This juice, which is 14% sugar, is distilled all the way down to type a extremely concentrated syrup, mixed with the pulp after which, taking sustainability to new ranges, blended with the dried husk, or endocarp, to type a really candy cocoa gel.

The gel, when added to the cocoa beans to make chocolate, eliminates the necessity for sugar.

Mr Mishra sees his invention as the most recent in a protracted line of improvements by Swiss chocolate producers.

Within the nineteenth Century, Rudolf Lindt, of the well-known Lindt chocolate household, by chance invented the essential step of “conching” the chocolate – rolling the nice and cozy cocoa mass to make it easy and cut back its acidity – by leaving a cocoa mass mixer operating in a single day. The consequence within the morning? Deliciously easy, candy chocolate.

Lindt

Lindt“You need to be innovative to maintain your product category,” says Mr Mishra. “Or… you will just make average chocolate.”

Mr Mishra was partnered in his undertaking by KOA, a Swiss start-up working in sustainable cocoa rising. Its co-founder, Anian Schreiber, believes utilizing all the cocoa fruit might resolve most of the cocoa business’s issues, from the hovering worth of cocoa beans to endemic poverty amongst cocoa farmers.

“‘Instead of fighting over who gets how much of the cake, you make the cake bigger and make everybody benefit,” he explains.

“The farmers get significantly extra income through utilising cocoa pulp, but also the important industrial processing is happening in the country of origin. Creating jobs, creating value that can be distributed in the country of origin.”

Mr Schreiber describes the traditional system of chocolate production, in which farmers in Africa or South America sell their cocoa beans to big chocolate producers based in wealthy countries as “unsustainable”.

Imogen Foulkes

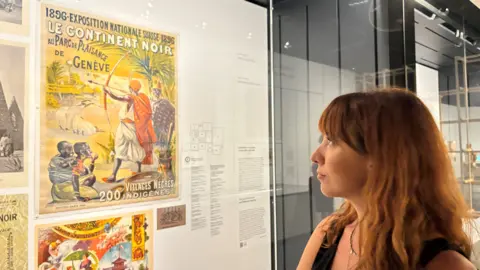

Imogen FoulkesThe model is also questioned by a new exhibition in Geneva, which explores Switzerland’s colonial previous.

To those that level out that Switzerland by no means had any colonies of its personal, chocolate historian Letizia Pinoja counters that Swiss mercenary troopers policed different international locations’ colonies, and Swiss ship house owners transported slaves.

Geneva particularly, she says, has a specific hyperlink to a few of the most exploitative phases of the chocolate business.

“Geneva is a hub for commodity trade, and since the 18th Century, cocoa was reaching Geneva and then the rest of Switzerland to produce chocolate.

“With out this commodity commerce of colonial items, Switzerland might by no means have change into the land of chocolate. And cocoa is not any completely different from some other type of colonial good. All of them got here from slavery.”

Nowadays, the chocolate industry is much more highly regulated. Producers are supposed to monitor their entire supply chain to make sure there is no child labour. And, from next year, all chocolate imported to the European Union must guarantee that no deforestation took place to grow the cocoa used in it.

But does that mean all the problems are solved? Roger Wehrli, director of the association of Swiss chocolate manufacturers, Chocosuisse, says cases of child labour and deforestation remain, particularly in Africa. He fears that some producers, in a bid to avoid the challenges, are simply shifting their production to South America.

“Does this resolve the issue in Africa? No. I assume it might be higher for accountable corporations to remain in Africa and assist to enhance the state of affairs.”

That is why Mr Wehrli sees the new chocolate developed in Zurich as “very promising… When you use the entire cocoa fruit, you will get higher costs. So it is economically fascinating for the farmers. And it is fascinating from an ecological perspective.”

Chocosuisse

ChocosuisseThe link between chocolate production and the environment is also stressed by Anian Schreiber. A third of all farm produce, he says, “by no means leads to our mouths”.

Those statistics are even worse for cocoa, if the fruit is abandoned to use only the beans. “It is such as you throw away the apple and simply use its seeds. That is what we do proper now with the cocoa fruit.”

Food production involves significant greenhouse gas emissions, so reducing food waste could also help to tackle climate change. Chocolate, a niche luxury item, may not by itself be a huge factor, but both Mr Schreiber and Mr Wehrli believe it could be a start.

But, back in the laboratory, key questions remain. How much will this new chocolate cost? And, most important of all, without sugar, what does it really taste like?

The answer to the last question, in this chocolate-loving correspondent’s view, is: surprisingly good. A rich, dark but sweet flavour, with a hint of cocoa bitterness that would fit perfectly with an after dinner coffee.

The cost may remain something of a challenge, because of the global power of the sugar industry, and the generous subsidies it receives. “The most cost effective ingredient in meals will all the time be sugar so long as we subsidise it,” explains Kim Mishra. “For a… tonne of sugar, you pay $US500 [£394] or much less.” Cocoa pulp and juice cost more, so the new chocolate would, for now, be more expensive.

Nevertheless, chocolate producers in countries where cocoa is grown, from Hawaii to Guatemala, to Ghana have contacted Mr Mishra for information about the new method.

Chocosuisse

ChocosuisseIn Switzerland, some of the bigger producers – including Lindt – are starting to use the cocoa fruit as well as the beans, but none, so far, has taken the step of eliminating sugar completely.

“We’ve to search out daring chocolate producers who wish to check the market and are prepared to contribute to a extra sustainable chocolate,” says Mr Mishra. “Then we are able to disrupt the system.”

Perhaps those daring producers will be found in Switzerland, whose chocolate industry makes 200,000 tonnes of chocolate each year, worth an estimated $US2bn. At Chocosuisse, Roger Wehrli sees a more sustainable, but still bright, future.

“I feel chocolate will nonetheless style incredible sooner or later,” he insists. “And I feel the demand will enhance sooner or later as a result of rising world inhabitants.”

And will they be eating Swiss chocolate? “Clearly,” he says.